“A Second Chance”

Metropolis Magazine, Steven Litt, October 2011

Cleveland, like many American cities, is inherently conservative in its architectural tastes, but it has always had its share of stubborn contrarians eager to flout local orthodoxy. One of them was William Hunt Eisenman, a founding member and the national secretary of a global clearinghouse for scientific and technical research on metals, plastics, and ceramics, which is known today as ASM International.

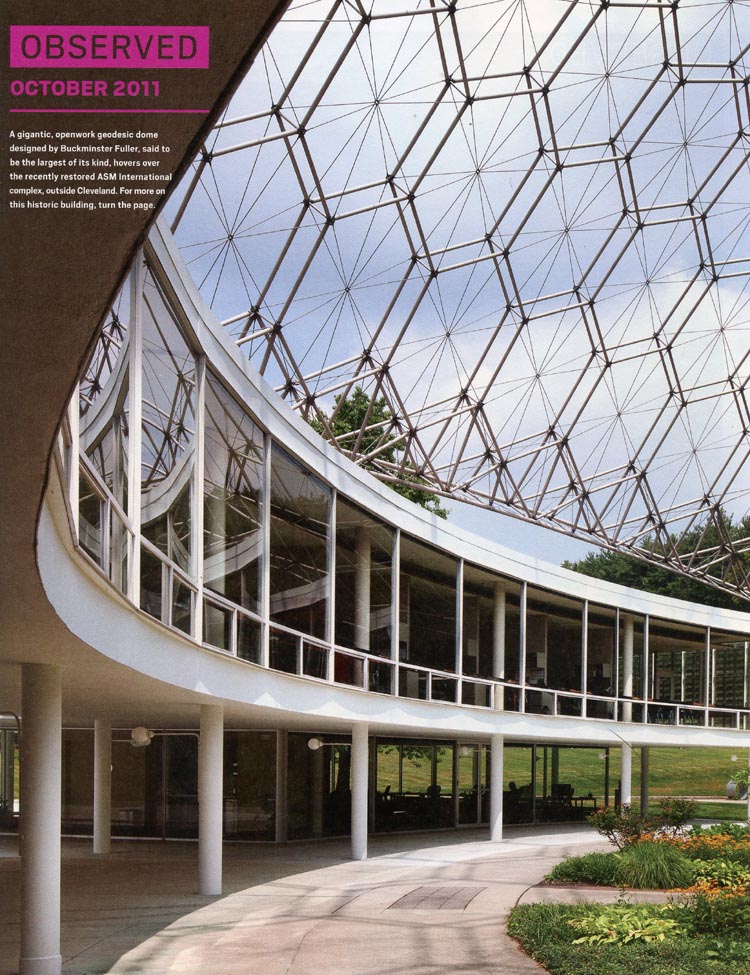

In 1959, the organization moved, at Eisenman’s behest, from downtown Cleveland to a strikingly futuristic new headquarters in semirural Russell Township, about 25 miles east of the city. It was designed by a thirtysomething Cleveland architect named John Terence Kelly, who had studied at Harvard under Walter Gropius, earning master’s degrees in architecture and landscape architecture. To realize his vision of a low, glassy, semicircular office pavilion, surmounted by a vast geodesic dome, and containing a circular garden in its center, Kelly’s first move was to recruit R. Buckminster Fuller, of Synergetics in Raleigh, North Carolina.

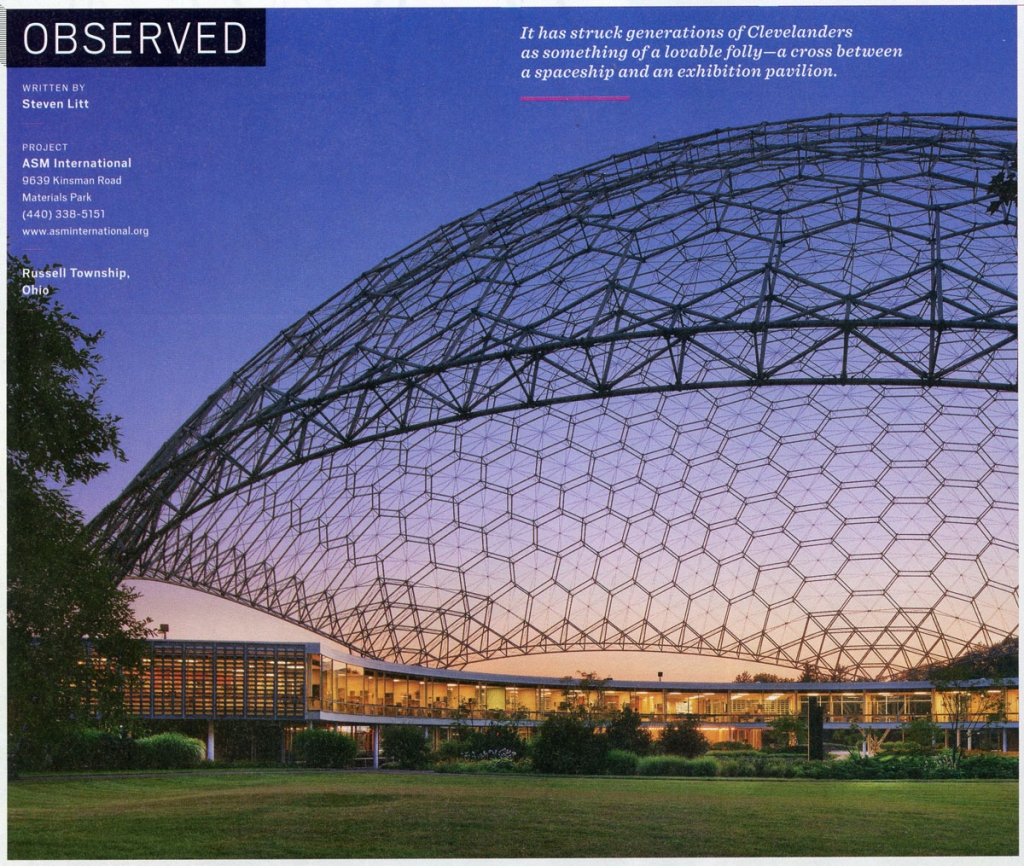

The result of this unusual collaboration was unlike anything else that had been built in northeast Ohio. It has struck generations of Clevelanders as something of a lovable folly—a cross between a spaceship and an exhibition pavilion that could have been airlifted from a world’s fair somewhere and dropped amid the rolling green hills, forests, and subdivisions along Ohio State Route 87.

A $7 million restoration and renovation of Kelly’s office building, completed last August, has not only returned the ASM complex to its 1959 appearance, but may well be a harbinger of how federal and state historic-preservation tax credits can be used to revitalize midcentury modern buildings. When the complex attained the threshold age of 50 years in 2009, Michael Chesler, the president and CEO of Cleveland’s Chesler Group, persuaded ASM’s board that the building, dome, and garden—known collectively as Materials Park—could be listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and thereby become eligible for $2.5 million in tax credits.

In the ensuing process, officials of the Ohio Historic Preservation Office, in Columbus, and the National Park Service, in Washington, D.C., required Chesler and ASM to preserve original materials considered fundamental to Kelly’s building, including its copper fin-tube radiators; the large, single-pane plate-glass windows; and the open-tread, stainless-steel stairways. Working with Dimit Architects, of Lakewood, Ohio, the Chesler Group restored Kelly’s original sense of transparency and spatial flow, while introducing contemporary workstations and furnishings. Fuller’s dome—which has been retuned periodically and is considered structurally sound—was not part of the project. “This is the next fifty years,” Chesler says, obviously pleased with the results. “This is the future of historic preservation.”

A skeptic could easily say that Kelly’s building is more a series of quotations than an original statement. Raised up on concrete pilotis and wrapped in floor-to-ceiling glass, ASM gives off heavy emanations of Gropius, Le Corbusier, and Gordon Bunshaft. On its exposed west facade, the building’s lower level is trimmed with molded concrete arches that nod heavily toward Frank Lloyd Wright’s Marin County Civic Center.

But to focus on details is to miss the point. What counts here is the totality of Kelly’s conception. The crescent-shaped office harmonizes beautifully with Fuller’s dome, which, at 250 feet in diameter, is said to be the largest openwork geodesic dome in the world. Kelly’s building encloses an expansive circular garden, which is laced with pathways, planting beds, and carefully labeled rocks and boulders composed of the minerals used to produce steel, aluminum, and other metals. The dome hovers overhead like a weightless cloud of steel hexagons. Kelly, something of a one-hit wonder, never again achieved anything as bold or exciting, which may explain, in part, why the ASM complex is so little known. But now, thanks to its recent renewal, it has a second shot at the wider attention it truly deserves.